Private Equity firms have a new set of takers for their portfolio companies: themselves. A peek into the what, why, and how of this new trend.

At the beginning of 2020, CapVest, a leading mid-market PE firm, put Curium – a French pharmaceutical group – up for sale hoping for a USD 3 billion exit. By mid-March, they knew their expectations would not be met as the buyers became wary about financing. CapVest retracted the process and found its solution in a continuation vehicle sponsored by itself and completed the sale.

When CapVest raised money for its “continuation fund,” it joined a growing list of PE firms creating liquidity by buying their own portfolio businesses. Blackstone, Audax Group, BC Partners, and Vista Equity Partners are among those few juggernaut buyouts groups.

In this article, we investigate this new exit option and understand its intricacies and implications for general and limited partners.

What are typical PE exit routes?

All PE transactions are structured with an exit in consideration. Investors would usually contribute to a PE fund to invest in a portfolio of companies and expect to get their investment back with profit (after the exit, i.e. selling the companies to outside buyers or taking it public), within a timeframe of 5 to 7 years (10 years at maximum).

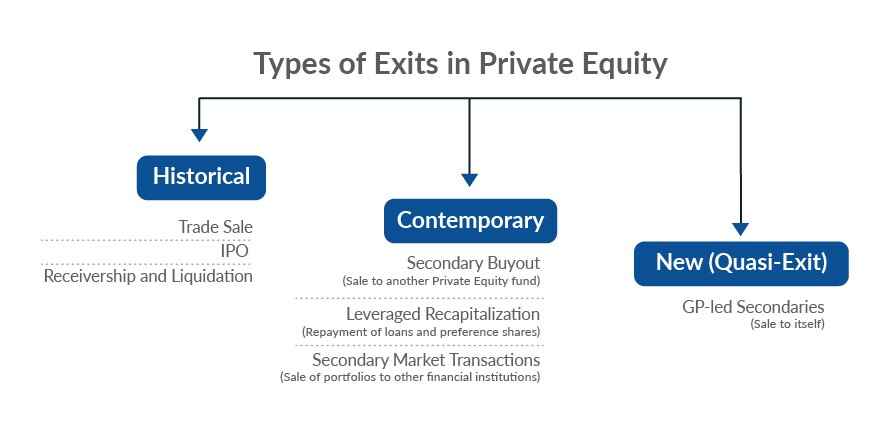

Historically, PE firms use to choose three routes to exit:

- Trade Sale: It’s exit by selling the portfolio business to a corporate acquirer.

-

IPO: It involves exiting by floating the company on a stock market. It is considered one of the best exit strategies by entrepreneurs and investors.

-

Receivership and Liquidation: This exit route is adopted when a company is recognized in bankruptcy or is to be liquidated. It’s usually the last resort for creditors to recover their debts.

Although, the above three are only cursory ways of understanding PE exits. Over time, more novel routes have emerged, which are often seen in practice. They include:

- Secondary Buyout: It is exit by selling to another private equity fund. It’s a Leveraged Buyout (LBO) where a previous private equity sponsor firm sells the target company to another PE sponsor firm.

-

Leveraged Recapitalization: It is an exit strategy wherein the target company restructures its capital structure by raising more debt for repaying loans and preference shares.

-

Secondary Market Transactions: It includes the sale of portfolio companies to other financial institutions or buyers in PE secondary market.

A new partial exit strategy that’s recently becoming popular is:

- General Partner-led Secondaries: In these exit deals, PE firms sell their portfolio of assets to another fund of their own – called continuation fund. Unlike sponsor-to-sponsor secondary buyouts, these deals involve sales from the older-to-newer fund. We discuss more about them in the next section.

The inception of new exit deals

When a fund approaches the end of its life (5/7/10 years), the fund manager must exit an investment. If the fund is extended beyond (even to maximize the value of investments), there are penalties incurred by the PE fund manager. Therefore, it is always more rewarding to sell when the time comes for whatever the present value (instead of waiting for longer-term).

The COVID-19 crisis disrupted PE funds’ ability to sell portfolio businesses and pay back the promised returns to investors on time as the corporate boards became warier of deals. As a result, an old, but scarcely used alternative exit became popular: GP-led secondaries. It allows general partners to raise new funds to buy portfolio businesses from their old funds.

These exit deals have many incentives for both private equity companies and investors, like:

- They allow PE firms to hold onto good portfolio companies for longer periods (especially since the competition has made hunting for new acquisitions more expensive and riskier).

-

In most instances, they trigger the carry from the old fund to be carried forward to the assets in new fund – allowing PE Fund managers to retain lucrative management fees.

-

They give limited partners and earlier investors an option to cash out or stay invested in the portfolio companies.

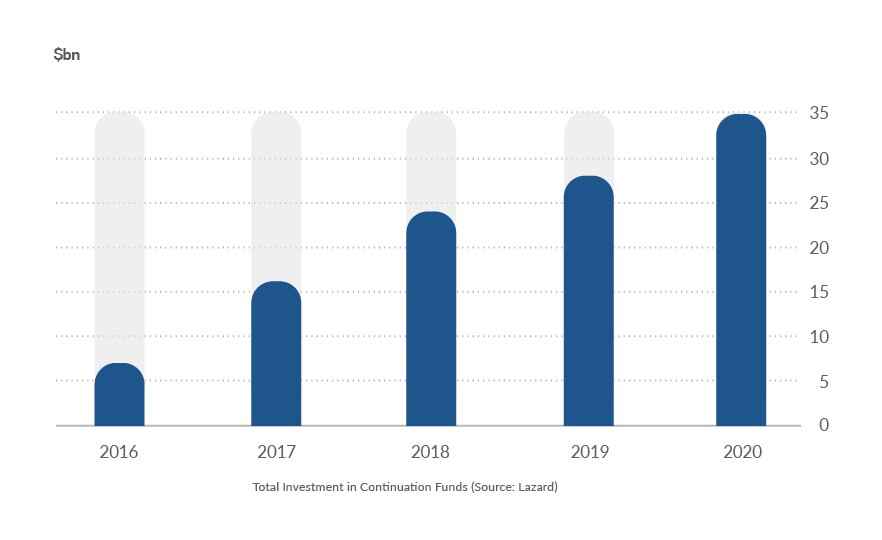

Such niche sets of deals where firms lean on to newer private equity fund (continuation fund) to facilitate exits from old deals have become mainstream in private equity. And according to FT.com, the momentum for these sidecar deals will build further in 2021.

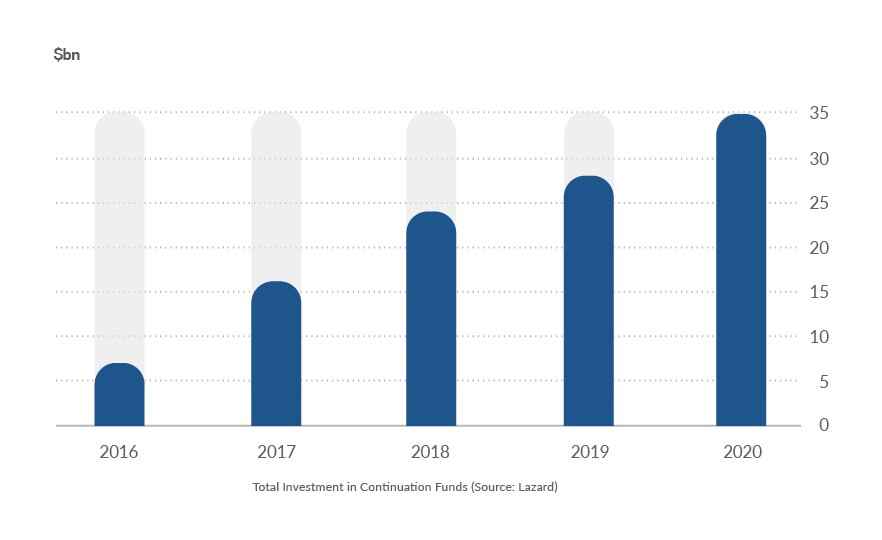

The value of these deals hit USD 35 billion in 2020, five times the value four years ago.

Continuation funds: How they work?

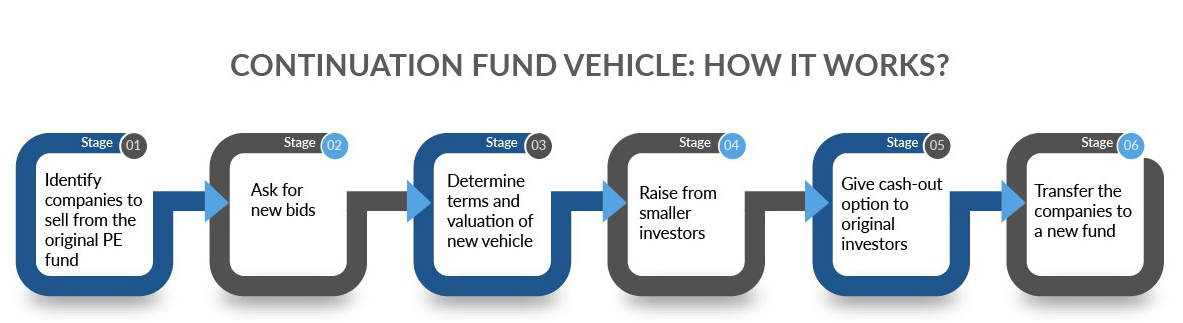

To execute the ‘sell to yourself’ exit strategy, PE firms create continuation fund and find investors to back them. Once that’s accomplished, they recommit the portfolio businesses already owned by one of its funds to this continuation vehicle.

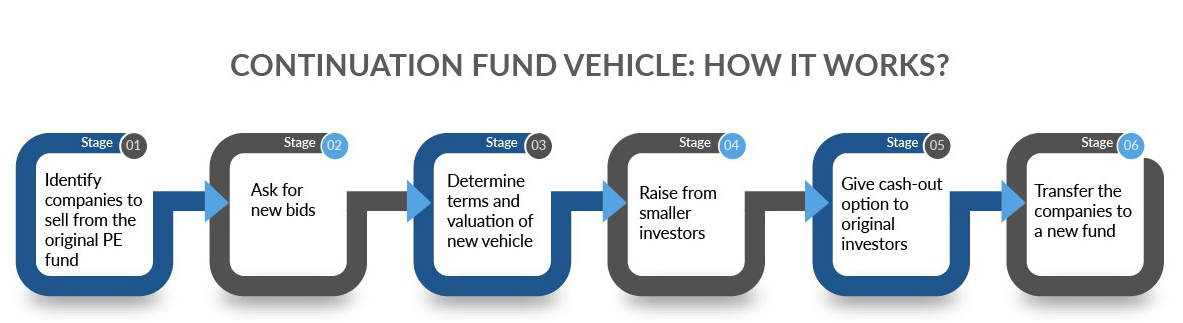

Secondary funds, specialist PE fund managers, and expert asset managers comprise the core team that raises new funds from institutional investors and others. A look at the six-stage process of making the sale through a continuation fund.

-

Stage One

The target portfolios are carved out from the original private equity fund.

-

Stage Two

Secondary funds are called upon to submit bids for continuation fund. At this stage, the PE firm presents its valuation of the target portfolio company or companies.

-

Stage Three

Secondary fund providers discuss their intended commitment to the continuation vehicle. The terms around management fees and carried interest are also determined at this stage, along with the valuation of the fund.

-

Stage Four

Book building begins after a few large players sign up. It is the process in which underwriters determine a fair price for the deal. Small investors are also approached at this stage to raise the rest of the money (as agreed by the larger players).

-

Stage Five

LPs and investors in the original fund are given an option to cash out or buy into the continuation vehicle. The PE firm and GPs also contribute some of their money to the new fund.

-

Stage Six

The target portfolio company or companies are transferred to the continuation fund.

What do LPs want to know?

These quasi-exit transactions raise many questions from investors – both original and new.

At the heart of the matter is the predicament: What’s a fair price when you sell something to yourself?

Since both the buyer and seller are controlled by the same PE firm, it becomes a problem. It is fine if a fair process is followed to value a deal and any conflict of interest is avoided. But, it’s difficult to reassert.

“Why do you want to keep this business?” and “How did you reach the price at which the portfolio business must be sold (valuation)?” – are the two most common questions asked by investors.

Investors are wary of executives offloading struggling companies. The carved-out companies could be a dog or a star. And if one is only selling the dog, it would make no logic to buy it. “A mix of star and dog (2:3), if not all stars, is usually a pragmatic continuation fund investment approach,” says a PE fund manager.

The risks for investors are two-fold:

- - Forfeiting an opportunity of making an extra profit by selling early or at a low price, and

-

- Buying an asset by overpaying as it may not deliver on the promised returns (and it may also mean paying double layers of management fees for some of the original LPs).

As the trend of continuation vehicle gathers pace, the question of valuation poses an inherent tension in these deals that is even drawing regulatory scrutiny. Management fees and carried interest are other few regulatory concerns.

Assuaging investor concerns

There are two ways investors deal with the risks and questions.

First, investors sometimes set up independent committees of their own to vet the profitability of the transaction, and any conflicts of interest.

Second, original PE funds at times take the lead in reassuring the investors that the agreed price represents a fair market value by running auctions – and inviting secondary fund firms to submit bids.

For instance, recently Blackstone conducted a “go-shop” process during the sale of BioMed Realty from one of its PE funds to see if bankers can beat the continuation fund’s offer with higher bids.

However, PE firms are not always forthcoming about their valuation process, and these sales are not put open to all potential outside bidders.

Summing it up

Exits are a vital part of the PE deal lifecycle for investors and by extension PE managers and executives. Private Equity professionals who run the show go by the motto of “think like an investor” in their careers.

Take the first step to understanding the wave of older-to-newer fund exits.

Demonstrate a practical knowledge of risk and reward dynamics of PE buyout and exit deals with USPEC’s Chartered Private Equity Professional (CPEP™) certification.