Private equity-backed buyouts, which dried up earlier this year as a result of the pandemic are witnessing a resurgence. The US institutional loan issuance tied to the Leveraged Buyout (LBO) deals rebounded to USD 9.5 billion in October, the second-highest monthly of 2020. It is time for those in the occupation to clear their trained eyes for spotting and engineering leveraged deals.

LBOs are the most mythical and heavily talked about deals of the financial town. Their eye-popping prices and hot leverages require intrepid private equity managers to lead these transactions. As exciting and huge their gains (as well as losses) are, as complex they appear to the uninitiated.

In this article, we take a detailed look at the general principles involved in leveraged buyouts and the structuring process – one of the coveted skills – of these attractive transactions.

LBO Deals: In Household Terms

The concept of leveraged buyouts is simple than it seems at the onset.

Every buyout transaction has two sides – purchasers (PE Funds) and owners (target company). The PE funds require a lot of money to buy undermanaged companies. Thus, they lean on banks (and other providers) for financial support, who in turn, expect the company to make enough sum to pay back the financiers and profit shareholders.Since a significant portion of these deals is realized through (banks’ and other providers’) debt, they are called Leveraged Buyouts (LBOs).

In a nutshell, LBOs provide an alternative for stressed companies to restructure their ownership and control and stay afloat by using investible cash facilitated by PE funds to finance the target company.

Financial engineering is thus a core skill for private equity professionals. It outlines an optimal structure for financing an afflicted company. At its most fundamental level, it answers: How much is it advisable for a strained business to borrow from a bank or other lenders?

Valuation & Financial Engineering

In practice, determining a capital structure is very complex for PE managers. The resultant structure must be such that sufficiently finance the business’s growth plans after the acquisition, accommodate the vagaries of the market, and reward investors as well with strong returns for the risk taken by them.

The first goal, therefore, of an LBO deal structuring is to determine the value of the company – in relation to the debt required for the transaction. The worth is understood from:

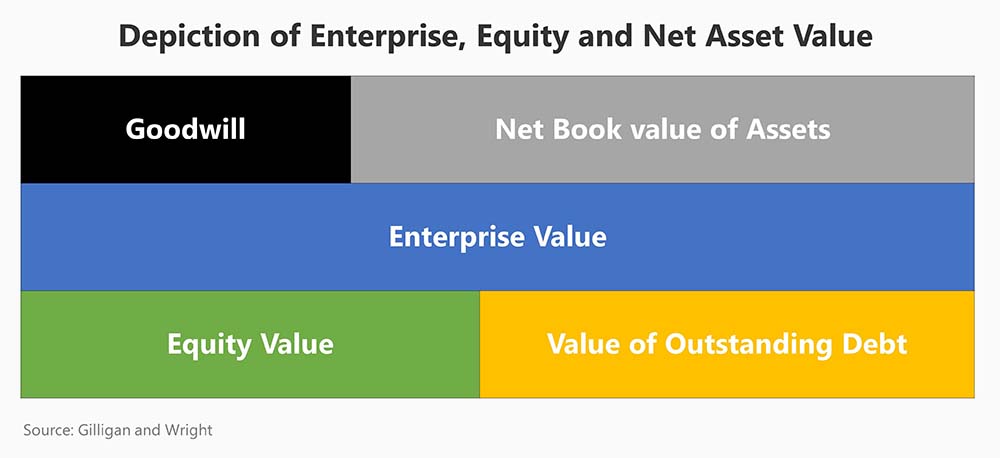

Equity Value: It is the value of a business after deducting debt and other claims. It can be measured through the P/E ratio.

Enterprise Value: It reflects the company value irrespective of how it is financed. It is measured by EBIT, EBITDA, and other methods. It can be called the operating value of a business.

Net Book Value of Assets: It represents the company’s value in the books minus intangibles such as goodwill, patents, and debt liabilities.

Valuation goes hand in hand with financial engineering strategies, which derive a company’s potential value in periods following the acquisition and project a rate of return with different strategic combinations. A few capital structuring strategies, for instance, are:

Reducing weighted average cost of capital by taking larger debt, leading to a high yield to equity ratio.

Lowering capital costs by refiguring company’s assets through, say sale (or licensing) of intellectual property, implementing stringent work capital plans, sale of real properties or assets.

Combining stressed company’s assets with other businesses to expand its scale and incur higher value for a combined company. It is also called a roll-up strategy, often employed in the retail sector.

LBO Deal Structuring

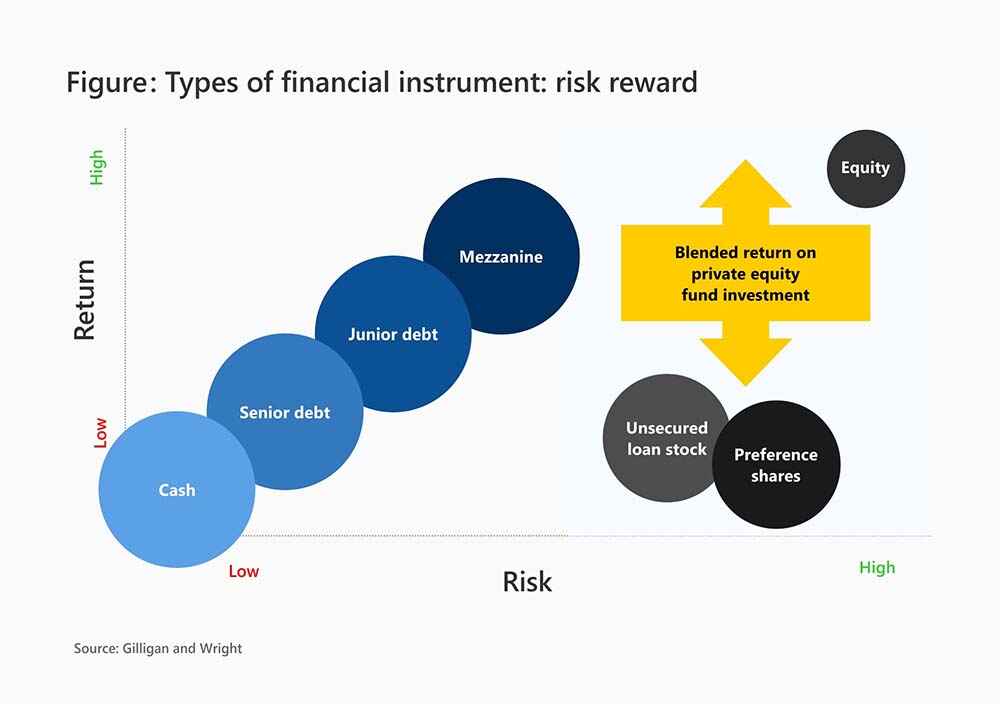

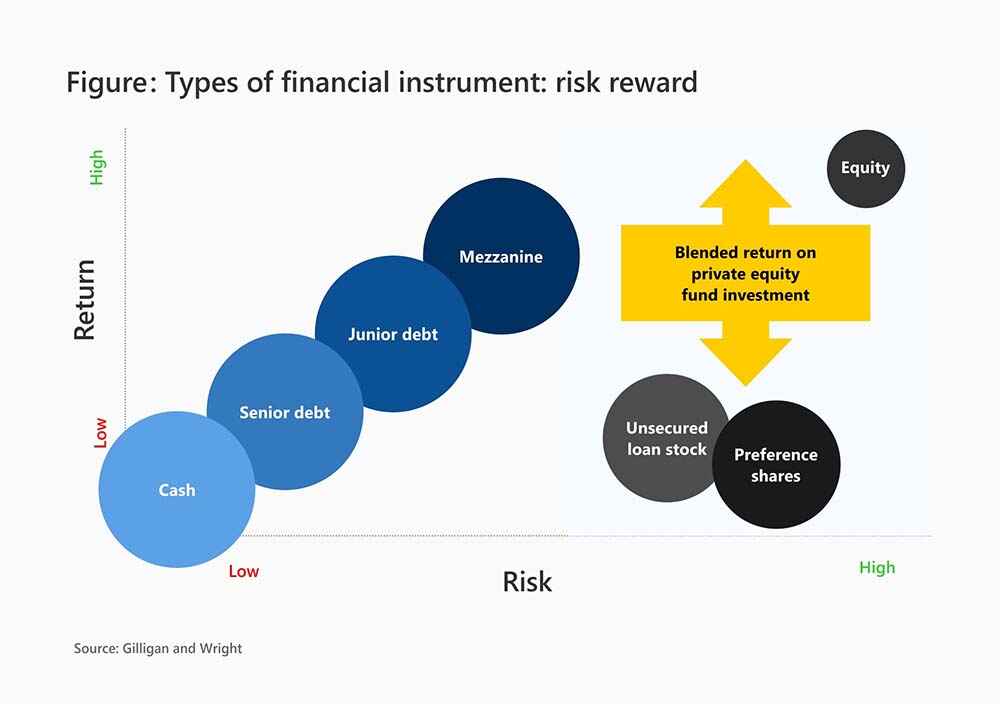

It is typical for the large buyout deals to be financed through multiple levels of debts with different associated risks and rewards. A look at the different combinations of financial instruments used for LBO deal financing.

Senior Debt

Senior debt has the topmost priority among all debts with respect to receiving interest or proceeds in case of insolvency. It is usually a loan from the bank. It has several safeguards for the lender, and thus offers a lower rate of return.

Risk: Low

Features

Mezzanine Debt

It offers a risk and reward profile that is above senior debt but below equity. It can be provided by special mezzanine funds or banks.

Risk: Medium

Features

Private Equity Fund(s)

Equity holders get the highest rate of returns owing to the high risks taken by them. Therefore, PE managers are the bulwarks who look closely at the working capital of a business and structure an optimal deal – via financial engineering and negotiations with other lenders.

Risk: High

Features

Restructure: When plans go awry

What do you do when the investment in a business doesn’t pan out as planned? Financial restructuring comes into play in such cases. It is the process of renegotiating a business’s financial structure to meet planned projections and alleviate the distress on the company. There are two types of distress that a company can face – operational (when enterprise value falls to zero), and financial (when equity value nears to zero). Restructuring is possible usually when an enterprise has a positive enterprise value, but falling or negative equity value.

These are the three interlinked, but individual reasons due to which the financing structure designed at the time of initial transaction can fall apart:

When cash flow from daily operations becomes negative. It implies loss-making, and that the business is spending more than it earns.

When positive cash flow is insufficient to fulfill funding requirements of the business. It occurs when one borrows more than it can repay.

When the debts fall due, and non-compliance makes it insolvent.

Four Common Restructuring Pathways

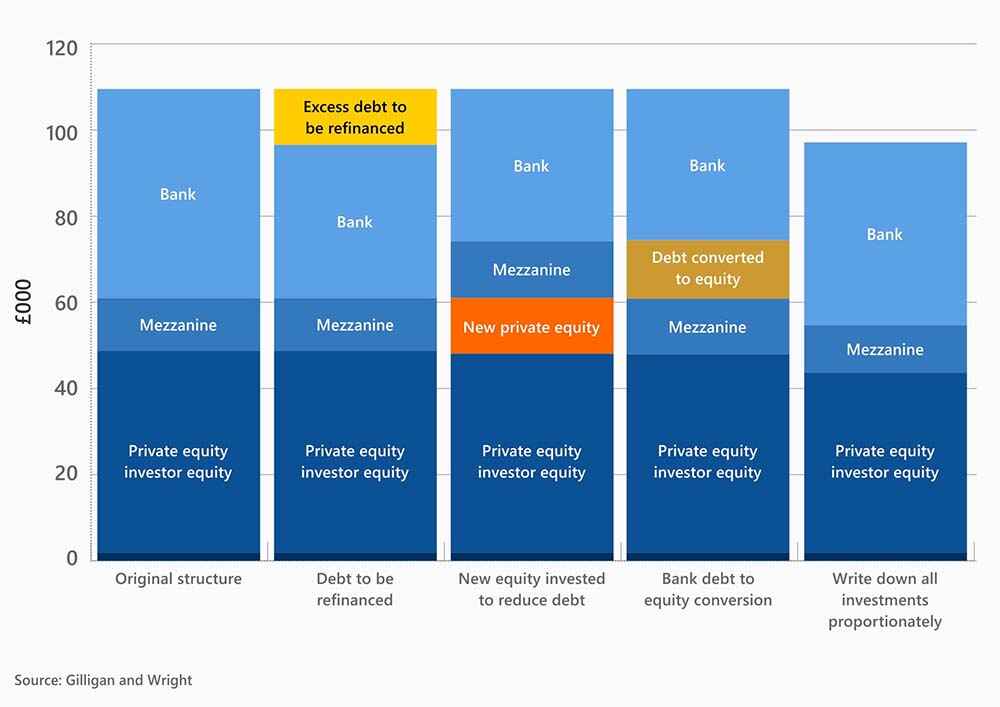

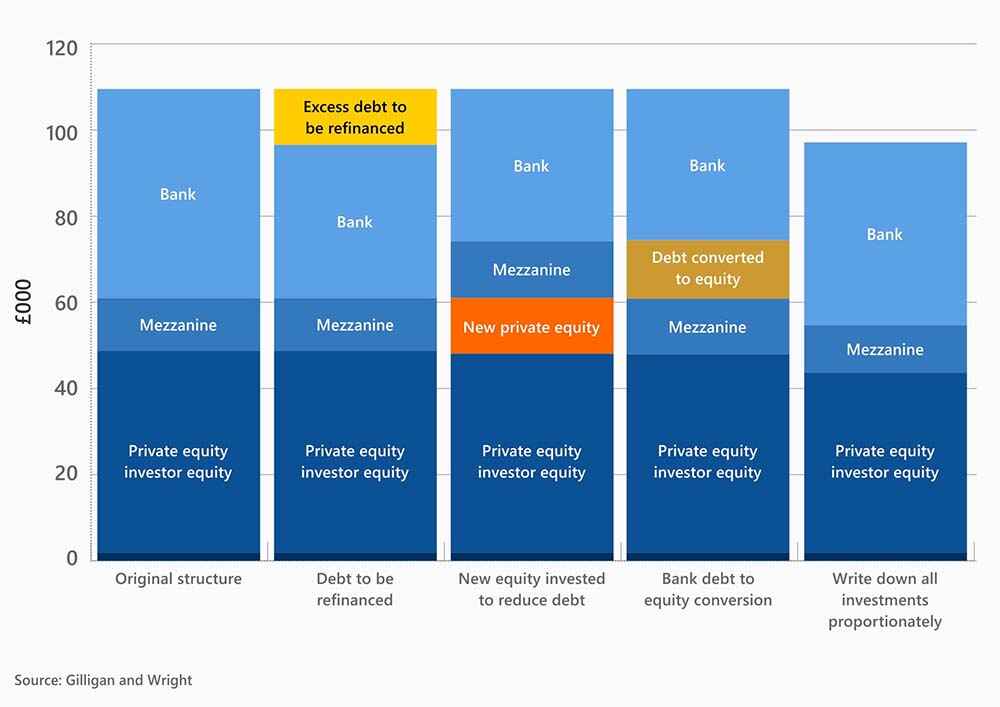

The prime question asked during restructuring by evaluators is – how much more can a business prudently borrow? Much due diligence is taken at this point to investigate what went wrong in earlier structuring. Sensitivity analysis is performed to reach sound judgment for the future. Overall, four versions of restructuring are seen.

1. Reschedule current debt

If the lender is convinced that the distress can be alleviated by rescheduling the debt repayments, then restructuring can be done by amending the existing debt covenants. Under this, the term of the loan can be increased. Since, this structure represents higher risks than earlier, a part of the loan is repackaged and repriced as a mezzanine.

2. Inject more equity

Infusing new equity isn’t so simple. It is unlikely that PE funds or lenders will undertake this option to reduce debt obligations of the business. However, if there are credible reasons that justify the move to inject new equity, it can be done by the banks. It enables quick restructuring.

3. Convert debt to equity

Banks receive the lowest return in PE LBO deal structures because they take the lowest risks. If it is perceived by them that their risks have become similar to that of PE investors and managers, it is not uncommon for the banks to reprice the debt, and convert their debt portion into equity holdings (thereby reducing equity holdings of other shareholders).

4. Write off some loans

Albeit a traditional practice, it is still used. If a company accumulates too much debt, then equity investors can negotiate with the banks and convince them to write off a part of the debt under overall restructuring plan. New equity may be injected as a result.

Whether private equity professionals will engage in structuring and restructuring is contingent on whether they can bolster the value of the businesses they invest in. Any structuring or restructuring requires a blend of sharp financial acumen and strong negotiation. Chartered Private Equity Professionals (CPEP™) bring to the table the skills and exposure to deal with complex financial states.